|

Louis Eustache Ude 'Le Cuisinier français' 1848 THE TASK of the Foods of England project is nothing less than to, first, rediscover and then to revive a whole lost cuisine. The food history of England is vast and, as that quote from the very, very French Louis Eustache Ude, says, English food once had a reputation unrivalled in the world. Why? Traditional foods are, by definition, made from local ingredients, and reviving them means giving support to local farmers, to local producers and it means getting down the food miles. A local food tradition creates a draw on which tourism, retailing and hospitality of all kinds can build. And keeping a hand on our history is just, simply, the right thing to do. Rediscovering that history is a bigger challenge than you might imagine - an awful lot of the old-time foods of ordinary people never got written down, so it can be quite a detective job for us to rediscover them. Here's just two little examples for starters...  Yorkshire woman making havercakes - note the drying rack top right From: 'The Costume of Yorkshire', by George Walker (1781-1856) The UK imports around 8,000 tons of crunchy, delicious crispbread each year, largely, of course, from Scandinavia and Poland and the Baltics, because that's where crispbread comes from, isn't it? Well, it does now, but there was once a whole world of 'haverbread', the crispbread of the English North and Lakes, sufficiently famous that soldiers recruited in Lancashire with the promise of "haverbread every day" were, in the 18th Century press 'Havercake Lads'. But this was common people's food, and nobody ever wrote down how to make havercake. We've been able to reconstruct them from scraps of news, the recollections of a few Pennine farmers and 'Havercake racks' still hanging from the ceilings of their farms. There's a fascinating history here, which could market a really, very, delicious product. So that's an example of a trade good, and we could add hundreds more lost ones from Suffolk Hard Cheese to Radish Pickles, or known-but-not-really-promoted ones like Dumpsie-Dearie and Bradenham Ham. Now, what about restaurant food?  Britain loves going to Italian restaurants, and Britain loves pasta, every year we import nearly half-a-million tons of macaroni, spaghetti, lasagne and the rest. And we assume it is an Italian thing, but there's a whole gallery of English pastas going back to the 1390's. There's Old English 'Loseyns', a puzzlingly familiar dish of layered pasta, meat and cheese, there's little pasta 'Tartlette' parcels, like the 'Pierogi' or 'Tortellini' of further East. And there's our home-grown 'Papdele ' - a form of English pasta shapes, which a correspondent (thanks Kathryn M!) tells us was still being made exactly to the medieval recipe into her grandmother's time. And instead of kebabs, how about some Skuetts, or a Sturmye instead of Paella? You could start off with some Whets, maybe an Exeter Oyster, or even a Fart. Feast on a sturdy plate of Panjotheram or just a light Frumenty? And afterwards, well, we've more puddings than you could possible believe.  |

|

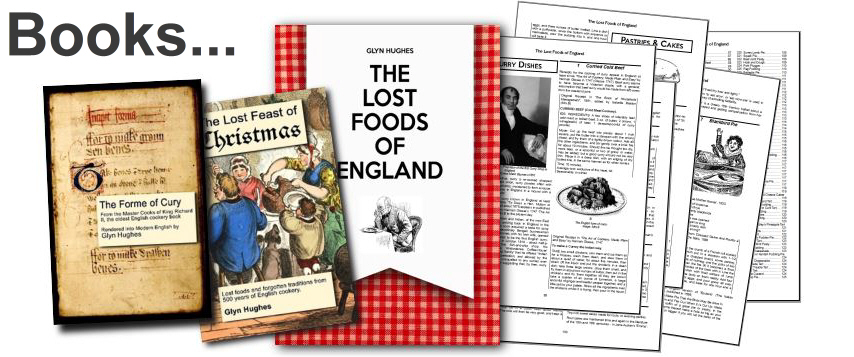

MORE FROM Foods of England... Cookbooks ● Diary ● Index ● Magic Menu ● Random ● Really English? ● Timeline ● Donate ● English Service ● Food Map of England ● Lost Foods ● Accompaniments ● Biscuits ● Breads ● Cakes and Scones ● Cheeses ● Classic Meals ● Curry Dishes ● Dairy ● Drinks ● Egg Dishes ● Fish ● Fruit ● Fruits & Vegetables ● Game & Offal ● Meat & Meat Dishes ● Pastries and Pies ● Pot Meals ● Poultry ● Preserves & Jams ● Puddings & Sweets ● Sauces and Spicery ● Sausages ● Scones ● Soups ● Sweets and Toffee ● About ... ● Bookshop ● Email: editor@foodsofengland.co.uk COPYRIGHT and ALL RIGHTS RESERVED: © Glyn Hughes 2022 BUILT WITH WHIMBERRY |